- History

- Pottery

- Industry

Wages in the Eighteenth Century

|

It was standard practice for many eighteenth and early nineteenth century industries to operate a practice known as annual hiring. Around Martinmas in November masters and workers struck deals for the following year’s employment. The employer paid earnest to secure the deal. Earnest could be a sum of money or a valuable article of clothing. Among the earliest records of wages paid to pottery workers in Staffordshire are Thomas Whieldon's memorandum notes. In 1752 he hired "Little Bet Blour to learn how to flower" at one shilling three pence per week. Whieldon employed Josiah Spode I in 1749. He was sixteen years old and to be paid weekly “2s.3d. or 2s.6d. if he Deserves it”. He was paid one shilling earnest to seal the deal, and promised two shillings nine pence per week in his second year and three shillings three pence per week in his third year. At the age of nineteen, in 1752, Spode was engaged at seven shillings per week with five shillings earnest. In 1754, Whieldon paid Spode seven shillings six pence per week with one pound eleven shillings and six pence earnest. Thomas Whieldon was the preeminent potter of his day, and while there is no reason to suppose that he was excessively generous, it is likely that he paid well. We have no record of the work Josiah Spode did for Whieldon, what ever it was it clearly prepared him for a successful career as a master potter. Wages had barely risen from an average of six shillings a week in the first half of the eighteenth century but as trade increased Staffordshire began to dominate the English pottery industry. As Staffordshire began exporting to all parts of Europe and the British colonies, workers wages rose. By the 1760s an average wage was nine shillings a week.

|

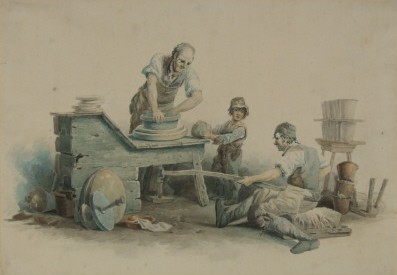

A thrower using an early crank wheel  "Flowering" in blue on a white salt-glazed stoneware mug Staffordshire, 1750-60Winterthur Museum 1958.934 |